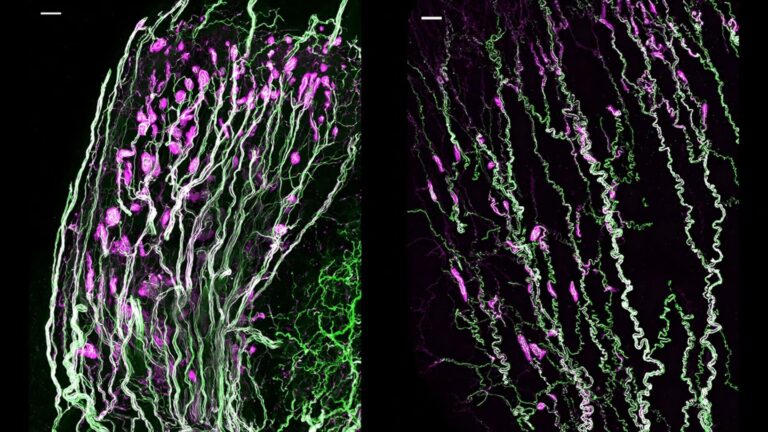

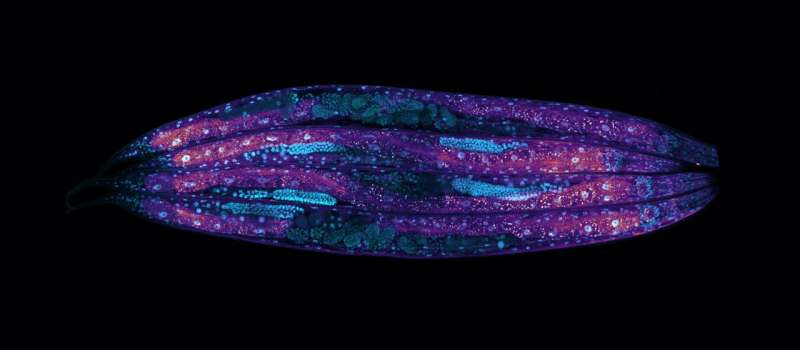

Composite image showing fluorescently labeled nuclei in each cell of five different C. elegans captured at the Advanced Light Microscopy Unit at CRG. Credit: Jeremy Vicencio, Nadia Halidi/Centro de Regulación Genómica

Why do some people live longer than others? The genes in our DNA sequence are important, helping to avoid disease or maintain overall health, but differences in our genome sequence alone explain less than 30% of the natural variance in human lifespan.

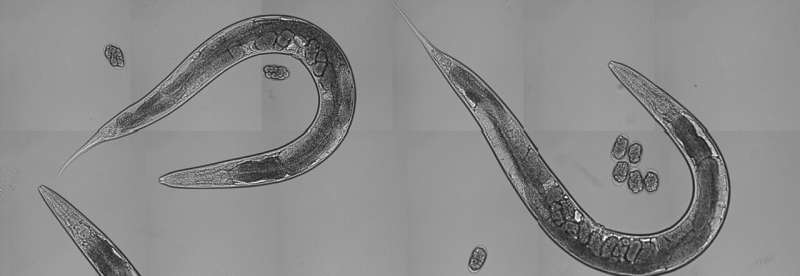

Exploring how aging is affected at the molecular level can shed light on changes in lifespan, but generating data at the speed, scale and quality needed to study this in humans is impossible. Instead, researchers turn to worms (Caenorhabditis elegans). Humans share a lot of biology with these tiny creatures, which also have a large natural variation in lifespan.

Researchers at the Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG) observed thousands of genetically identical worms living in a controlled environment. Even when diet, temperature, and exposure to predators and pathogens are the same for all worms, many individuals continue to live for a longer or shorter period of time than average.

The study traced the main source of this variation to differences in mRNA content in germ cells (those involved in reproduction) and somatic cells (cells that make up the body). The balance of mRNA between the two types of cells breaks down, or “breaks apart,” over time, causing aging to progress faster in some individuals than others. The findings are published today in the journal Cell.

The study also found that the size and speed of the detachment process is influenced by a set of at least 40 different genes. These genes play many different roles in the body, ranging from metabolism to the neuroendocrine system. However, the study is the first to show that they all interact to make some individuals live longer than others.

Knocking out some genes extended a worm’s lifespan, while knocking out some genes shortened it. The findings suggest a surprising possibility: the natural changes seen in aging worms may reflect randomness in the activity of many different genes, making it appear as if individuals are exposed to hits from many different genes.

“Whether a worm lives to day 8 or day 20 depends on seemingly random changes in the activity of these genes. Some worms seem to be just lucky, in that they have the right mix of genes. activated at the right time,” says Dr. Matthias Eder, first author of the paper and researcher at the Center for Genomic Regulation.

Knocking out three genes—aexr-1, nlp-28, and mak-1—had a particularly dramatic effect on lifespan variance, reducing the range from about 8 days to just 4. Instead of extending the lives of all individuals uniformly, knocking out every single one of these genes drastically increased the lifespan of worms at the low end of the spectrum, while the lifespan of the longest-lived worms remained more or less unchanged.

C. elegans photographed under normal color conditions under a microscope. Credit: Jeremy Vicencio, Nadia Halidi/Centro de Regulación Genómica

The researchers observed the same effects on health lifespan, the period of healthy past life, rather than how long an individual is physically alive. The researchers measured this by studying how long the worms maintain vigorous movements. Knocking down just one of the genes was enough to disproportionately improve healthy aging in worms at the low end of the health-span spectrum.

“It’s not about creating immortal worms, it’s about making aging a fairer process than it currently is—a fairer game for everyone. In a way, we’ve done what doctors do, which is taking worms that would die sooner than their peers and making them healthier, helping them live closer to their potential lifespan, but we’re doing it by targeting the underlying mechanisms of aging, not just treating sick individuals Nick Stroustrup, senior study author and group leader at the Center for Genomic Regulation.

The study does not address why knocking out the genes does not appear to negatively affect the worm’s health.

“Several genes may interact to provide built-in redundancy after a certain age. It may also be that the genes are not necessary for individuals living in benign and safe conditions where worms are kept in the laboratory. In the harsh environment of wild, these genes may be more critical for survival, these are just some of the working theories,” says Dr. Eder.

The researchers achieved their findings by developing a method that measures RNA molecules in different cells and tissues, combining it with the “Lifespan Machine,” a device that tracks the lifetimes of thousands of nematodes at once. The worms live in a petri dish placed inside the machine under the watchful eye of a scanner.

The device images the nematodes once an hour, gathering lots of data about their behavior. The researchers have plans to build a similar machine to study the molecular causes of aging in mice, which have a biology that more closely resembles that of humans.

More information:

Matthias Eder et al, Systematic mapping of organism-scale gene-regulatory networks in aging using population asynchrony, Cell (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.05.050

Cell

Provided by Center for Genomic Regulation

citation: C. elegans study reveals mRNA balance in cells affects lifespan (2024, June 21) Retrieved June 22, 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-06-elegans-mrna-cells-lifespan. html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for any fair agreement for study or private research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.